|

| Realist painter Lucian Freud, one of Britain's most distinguished and highly regarded artists, has died aged 88. | | | | | | |

| 10 THINGS YOU DIDN'T KNOW ABOUT HIS PAINTINGS |

|

|

|

By Florence Waters

The Telegraph

22nd July 2011

Almost all of us carry an image of a ‘Freud’ around in our minds – a gracelessly posed, grossly sagging woman, perhaps, or a face sculpted in paint that appears to fold and puff like a cauliflower ear. We all think we know his painting but, beneath the thick lashings of paint, there are a great many things to be discovered:

1. Freud’s paintings are autobiographical. Almost all the people he chooses to paint tell a story about himself and his values (he rarely worked on commission).

2. Freud has only once ever, he recalled, completed a portrait of a person he did not like, a book dealer called Bernard Breslauer. He so disliked the model that he was deliberately unkind and over-egged the pudding of a man in front of him, making him “even more repulsive than he actually was”. The unhappy sitter, on acquiring the portrait, sent Freud a letter saying that he had “contravened an unwritten contract between painter and sitter.” The painting in question was destroyed by the model.

3. Freud did not begin to employ thick sculptural brushstrokes until later in his career, a decision which lost him some important supporters in the art world at the time.

4. Freud knew a great many artists but remained a great individualist and did not bow to other talent: he remembers Picasso as “absolutely poisonous”, Man Ray as “noisy and vulgar”, and German expressionist Max Ernst as a “heavy and stiff” dinner companion.

5. Freud had an almost visceral hatred of almost all art of the Renaissance. It makes sense: the Renaissance was the period, above all, during which man was celebrated as the crown of creation. Freud’s belief was the opposite: man, he seems to say, must never forget the fact that he is deteriorating matter. It was Kant who first observed that an aesthetic encounter can be one that is mixed with pain, and Freud proves it eloquently.

6. Freud disliked art that looks too much like art. On sitting for a Freud portrait the art critic Martin Gayford remembered that “the awkwardness that critics complain of in LF’s work is deliberate.” A 1950 painting in the Tate Britain called ‘Boy Smoking’, for example, is not a realistic portrait. The eyes are glassy and hollow, the face so flat you could tear it. But the flatness here tells us something of the boy’s circumstances: it is as if a hard expression has been ironed in place on his youthful skin. Freud met the boy, named Charles Lumley, when he and his brother were “in the act of breaking into his studio”. Freud was living in Paddington, a working-class area at the time, and he befriended some of his criminal neighbours

7. Freud famously painted a rather unflattering portrait of the Queen and celebrities like Kate Moss, but he also admired – and loved to paint – friends and scallywags, including a “very clever bank robber” (his words) who is now immortalized as a scar-faced man in a Lucian Freud called ‘A Man and His Daughter’ (1963-4). One’s overwhelming impression of that picture is that it was painted with a great deal of respect.

8. Freud used to say that time was his one great luxury in life. He took a great deal of time to get to know his subjects, and sometimes would be paintings them for years. He asks that of his audience too: every Lucian Freud portrait has a different presence, requires time to get to know.

9. Freud rarely talks about his art. He almost always refused interviews and, aged 81 at the time the conversations in this book were recorded (2003-4), it had taken him his 49 year career, he says, to “know that the main point about painting is paint: that it is all about paint.”

10. Freud saw every object in the world as possessing a unique character. Even into the sixtieth decade of his career, he still celebrates the unique history of each material thing he drew and painted. It is his acute sensitivity to the multitudinous variety of ‘being’ that kept him invigorated by his work.

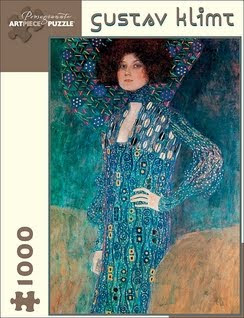

Emilie Floge Jigsaw Puzzle

Emilie Floge Jigsaw Puzzle

Boxed Embossed Notecards

Boxed Embossed Notecards

L'ile d'Abel by William Steig

L'ile d'Abel by William Steig

Win superb and fun time Knowledge Card Deck: Who Am I? A Name Game of Literary Stars.

Win superb and fun time Knowledge Card Deck: Who Am I? A Name Game of Literary Stars. Cat Wearing Bird Disguise B.Kliban 1935-1990

Cat Wearing Bird Disguise B.Kliban 1935-1990 Geese and the Moon by Ohara Koson [Shoson) 1887-1945

Geese and the Moon by Ohara Koson [Shoson) 1887-1945

Their shop is a delight and they also offer a mail order service for Jigsaw Puzzles:-

Their shop is a delight and they also offer a mail order service for Jigsaw Puzzles:-

Just two of our Sierra Club Christmas Cards available in boxes.

Just two of our Sierra Club Christmas Cards available in boxes.